After Islet Transplant, Glucose Control is "Amazing"

Alison Wesley received her diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes when she was just 11 years old, after she developed the classic symptoms of the disease – severe weight loss, excessive thirst, sugar cravings, frequent urination, and feeling lethargic. To treat the diabetes, doctors put her on the first generation of insulin pumps. She continued to use the pumps off and on until she was in her early 30s. But eventually, even the pumps could no longer help her control her glucose.

"I developed 'brittle diabetes'," she explains. "My glucose levels were swinging up and down. I was checking them five to ten times a day, and it was really challenging to normalize them."

Wesley, now 39 and a PR manager at Intel in Santa Clara, read about a clinical trial in islet transplantation being held at UCSF's Islet and Cellular Transplantation Facility. "I went to my endocrinologist," she said, "and immediately asked, 'could I be a candidate for this'?" Her doctor, Martha Kennedy, MD, told her she could, in part because her glucose was so poorly controlled at that point and she had tried all the traditional methods to maintain tight control, without luck.

After having two transplantations in 2010, Wesley now describes her glucose control as "amazing" and said her A1C level (which is a measure of average blood glucose levels over two or three months) is half of what it used to be and on the low end of normal.

Because transplantations carry some risks, Wesley said she did "a lot of research and a lot of soul searching" before electing to have the surgery. But "for people who are unable to control their glucose levels, who are having seizures, collapsing, constantly worrying that their levels are going to go too low and they're going to pass out," she adds, " this is invaluable."

The Transplantation Process

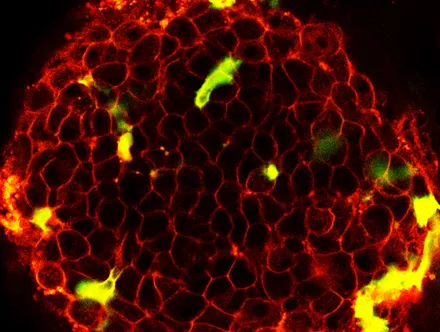

Wesley is one of about two dozen type 1 diabetes patients who have received islet transplantations to help her manage her disease since UCSF's program was founded nine years ago. In type 1 diabetes, the body's immune system destroys the body's insulin-producing islet clusters, making it difficult to maintain stable blood sugar levels. During the transplantation, doctor transfer islets (which are clusters of cells) that have been processed from a donor pancreas into the patient's liver, so that they can begin making and releasing insulin there.

"This procedure doesn't work for type 2 diabetes because in that disease, the body makes insulin but just can't use it correctly," explains Andrew Posselt, MD, PhD, who leads UCSF's Pancreatic Islet Transplantation Program. "So giving a patient more insulin-producing islet cells wouldn't do much good."

The Pros and Cons of Transplantation

Deciding whether or not to have the transplantation can be tricky. Side effects can include gastro-intestinal problems, blood clots, and the many known and unknown side effects of immune-suppressive drugs, including mouth sores, high cholesterol, anemia, infection and a higher risk of cancer. But in exchange, essentially all patients experience dramatically improved glucose control, and most achieve insulin independence. In addition, the improved glucose control may help avoid some of the long-term health effects of chronic diabetes, such as eye damage, nerve damage, kidney damage, and cardiovascular disease.

"It's a hard question to weigh," Posselt said. "But I think the best way is to ask, ‘how severe is the patient’s disease'? Some people really have trouble with day-to-day function because of their diabetes. They may be unable to control their blood glucose levels despite frequent blood checks or unable to feel when the levels are getting very low. Those people are at risk of passing out unexpectedly, such as while driving, or while sleeping. There is definitely a benefit for these people."

The risks associated with islet transplantation are also lower than the risks associated with a pancreas transplant, Posselt adds, in part because the islet procedure is less invasive than a whole organ pancreas transplant and doesn't require general anesthesia.

Wesley is quick to point out that this isn't a miracle procedure. "The goal with this procedure shouldn't be, 'I don't want to be diabetic anymore,' because that's not realistic. You are lessening the long-term impact of low blood sugar, but you still need to see doctors and watch your diet and take multiple medications. You're caring for yourself in new ways."

Hurdles to Islet Transplantation

The primary hurdle now isn't so much the availability of enough islets (i.e., pancreas donations), as figuring out how to keep them working well in the long-term, Posselt said.

"Twenty to thirty years ago, only five percent of people getting islet transplantation could achieve insulin independence," he said. With the Edmonton Protocol (which introduced new combinations of drugs to suppress immune responses to the islet cells), more than 85 percent can be insulin-independent at one year after transplant. Still, after an additional year or two, many patients begin to lose islet function. No one yet understands the slow decline in islet function. It could be related to rejection of the islets or a progressive loss of islet numbers.

However, "with changes in our transplant and immunosuppressive protocols, we are starting to see patients who are are insulin independent four and five years after their procedure", said Posselt.

“Islet transplantation can make a real difference in a patient’s life. The islet transplantation program at UCSF has been at the forefront of this new technology and continues to improve the protocol so that patients can live a healthy life with great glucose control”, said Matthias Hebrok, PhD, the Director of the UCSF Diabetes Center.

New Trials

Currently, UCSF researchers are conducting three new clinical trials for islet transplantations. Two focus on type 1 diabetics who have had the procedure and had no other transplants. The purpose of the first study is to determine the safety and effectiveness of islet transplantation combined with immunosuppressive medications in patients with type 1 diabetes who are experiencing both severe hypoglycemic episodes and hypoglycemia unawarenesss. The second study is to test the safety and effectiveness of one particular immunosuppressive drug (eoxyspergualin) on type 1 diabetes patients who have already had an islet transplantation.

The third study looks at how well islet transplantations work in type 1 diabetes patients who have already had kidney transplants.

"This is really important research," Posselt said. "Islet cell transplantation could help a lot of people who have severe diabetes but may not be candidates for pancreas transplants."

The story was originally published on the UCSF School of Medicine website and is reproduced here with permission.